Vodafone’s glass-half-empty CEO out to improve your phone signal

Sir Chris Gent, the swashbuckling chief executive credited with transforming Vodafone from the small arm of an electronics business into a giant of the telecoms world worth £80 billion, was a man rarely seen without his pinstripe suit and a pair of red braces.

Margherita Della Valle, the fourth person to step into Gent’s sizeable shoes 20 years after he exited the business in its early-noughties pomp, has a rather different style. When I pay a visit to the Italian’s spacious and plain office in Vodafone’s no-frills global HQ in Paddington, central London, I find her kitted out in a flowery beige jacket, and a pair of shiny designer trainers.

Della Valle’s eyes light up when I ask her about them. She ditched her old work shoes when she injured a ligament in her foot a while back. “And now, I think I’m never going to give them up,” she beams, proudly peering down at the shoes in which she walks 50 minutes to work every day. “If you go back 30 years, very different,” she adds, noting how sartorial standards have softened in the corporate world. “Now, we can do what we want.”

Della Valle, 59, is a Vodafone lifer. She joined Omnitel Pronto Italia, the company that became Vodafone Italia, as a marketing analyst in May 1994. That company was swallowed up by Gent’s behemoth, and in 2007, Della Valle was moved to the mothership, initially as European finance boss. She worked her way to become group chief financial officer in 2018 before landing the top job last year.

Although Vodafone has fallen some way from its millennium peak — these days, it’s valued at about £20 billion — the company remains a giant of the telecoms sector. An employer of 86,000, it last year brought in revenues of €37 billion (£31.5 billion) by selling mobile and internet services to 330 million customers in 15 countries across Europe and Africa. It has partners with networks in 43 other nations.

As the boss, Della Valle stands comfortably as one of Europe’s most significant female chief executives. Was this always the master plan? “It never was,” says Della Valle, who adds that she has always taken jobs within Vodafone that allowed her to do “interesting things” and make an “impact”. Della Valle, who grew up primarily in Rome but finished her school life in Monaco after a family move, retains her Italian accent. But she has mastered corporate English: our conversation is littered with “fireside chats”, changes “actioned” and “customer pain points”.

Vodafone’s geographical spread means that Della Valle, who has two sons in their 20s and recently became an “empty nester” with her retired banker husband Alessandro, spends much of her time abroad. Della Valle has both business and travel in her blood. Her father ran a small business, now taken over by her brother, which sold healthcare equipment. And her grandfather, Carlo, served as president of the Italian Geographic Society. Della Valle herself is an “armchair explorer”, who spends much of her reading time with books about polar exploration.

When Della Valle was unveiled as the successor to Vodafone chief executive Nick Read, on an interim basis in January 2023 and as full-time from April of that year, her long-standing association with the business counted against her in some quarters. Read, another company man, had overseen a 45 per cent drop in the share price to over four years to 84p, and Della Valle was a key cog in his machine.

She had also risen through the ranks under Vittorio Colao, a chief executive who left in 2018 with many admirers but also a fair amount of debt after completing an €18.4 billion deal to buy Liberty Global’s cable networks in Germany and several other eastern European companies. Karen Egan, head of telecoms at Enders Analysis, says Vodafone bought this business “at the peak of its operational performance” and the deal “left them in a precarious position from a leverage perspective, and that became a huge distraction for management when Nick Read took over”.

Della Valle’s challenge is to convince the City that, despite bearing the resemblance of a continuity candidate, she is the woman to transform Vodafone into a business more akin to the beast left behind by Gent back in 2003. “I don’t think I need to convince,” says Della Valle, who crafts her vocabulary carefully. “I think I need to act. I was very, very clear when I started that we needed to change a lot.”

Understandably, Della Valle is keen to draw a line between herself and the past, making quite clear throughout our conversation that she feels the company had become unruly, complex and disconnected from customers. When I ask her to name the best chief executive she’s worked under, she isn’t having any of it. “Unfair question,” she shoots back with a smile. “Really unfair.” Instead of answering, she opts for the “Pollyanna” route of telling me she feels “fortunate and blessed” to share a company with many great colleagues.

The Financial Times recently reported that Della Valle was working to eliminate a “macho culture” that had perpetuated inside her company. She dismisses this description. “I think that Vodafone has always been very diverse, to be fair,” she says, pointing to her own ascent.

“We are shooting for 40 per cent women leaders in this business,” she adds, a target that has nearly been reached. Part of the reason she thinks this is important is to provide more diverse role models for up-and-comers. “It’s important that women don’t only get advice on how to become like men, which used to be the case, but also get a sense of what it is to deliver a good leadership style that is not necessarily a macho-man leadership style.”

Vodafone’s share price fall continued largely unabated in Della Valle’s first year. In March, when I met Xavier Niel, the French telecoms billionaire who has built a 2.5 per cent stake in Vodafone, he was scathing of the management, said he couldn’t fathom the strategy, and mourned the loss of the “entrepreneurial spirit” of the early 2000s.

But, of late, there have been signs of life. Last month Vodafone surpassed expectations with its full-year results and the same day completed the €5 billion sale of its Spanish arm to Zegona, a London-listed shell company. Shares have been spirited up seven per cent so far this year to 75p.

When I ask Della Valle how she thinks investors are feeling about her performance, she folds her arms and frowns. “The way you’re asking the question seems to imply it’s about me as a person,” she says, sounding stern, “as opposed to Vodafone as a company? I don’t think investors are interested in people that much. They’re interested in results and facts.”

Even her harshest critics would struggle to argue that Della Valle has shied away from shaking things up. Under her guidance, Vodafone has cut 11,000 jobs, halved its dividend, invested in building up its customer base of businesses, sold off the Spanish business, agreed an €8 billion sale of Vodafone Italia, and agreed to merge its UK business with Three.

The latter deal would combine the nation’s third (Vodafone) and fourth (Three) largest mobile network operators to create a major competitor to BT’s EE and Virgin Media O2. European regulators, including the UK’s Competition & Markets Authority, have historically favoured their markets having four competitors rather than three. So the companies have a battle on their hands.

Vodafone and Three argue that they are currently unable to make a sufficient return on their investments in the UK, and that this has held them back from improving infrastructure and technology to improve their networks for users. They argue that a merged company, with close to 30 million customers, would make the necessary returns on capital and have pledged to invest £11 billion to “build a best-in-class 5G network”.

The argument goes that this, in turn, will force rivals to invest more, and create better competition for mobile providers like Sky and Tesco Mobile, which piggy-back off the networks of EE, O2, Vodafone and Three.

Della Valle comes armed with some alarming statistics to support her case. Earlier this year, research from Opensignal ranked the UK 22nd out of 25 European countries for 5G mobile internet availability and download speeds. For the study, Opensignal found that UK users had access to 5G 8.4 per cent of the day, versus 24 per cent in Bulgaria, the top-performing country. The UK’s average download speed was 118.1 megabits per second, versus 301.8 in Denmark, the top of that ranking.

And, says Della Valle, Europe as a continent, in large part because of the “fragmented” nature of the markets, does not compare favourably with the US and regions. “I think what people don’t appreciate at this stage is the cost that this implies for European countries,” she says. Consumers might not necessarily notice, but she says businesses are missing out. “You need automation, you need speed, you need low latency — you need 5G networks,” she says. Della Valle is targeting business-to-business — selling connectivity services to the corporate world — as a major area of growth for Vodafone.

Beyond large-scale mergers and acquisition activity, Della Valle has also, more quietly and behind the scenes, gone about trying to transform the culture inside Vodafone. Starting in Stoke-on-Trent. “If I think of Vodafone UK, that’s where my mind goes,” she says wistfully of the old northern city of pots, a home to the company’s largest customer call centre.

Della Valle has made it a priority to provide customers — both individuals and businesses — with a “good basic service”. To this end, Vodafone has extended its call centre closing time from 8pm to 10pm, and she says that average waiting times to answer have been reduced from 67 seconds to 14 seconds. “It’s not rocket science, by the way,” Della Valle adds. But she feels that Vodafone and the telecoms sector has not “excelled” on this front in the past.

Vodafone’s “shared operations” arm is also under the chief executive’s microscope. The division, which is responsible for providing back-office services such as IT and invoice-processing to the company’s operations across the world, has borne a large chunk of Della Valle’s job cuts. She says she wants to shift workloads, and “accountability”, to leaders of international divisions to avoid “ping-pong decision-making”.

What next for Vodafone under Della Valle? When I ask if more redundancies are on the way, she swerves the question, pointing out that her previous round of cuts is not yet complete. More large sell-offs or deals after Italy, Spain and the UK? “No, we are done,” she says. “When I became CEO, I said we had three markets to sort out.” She’s hopeful that Vodafone’s other national markets are set up well for growth in the future, while B2B sales should also increase.

But more pain is on the way in Germany, a market that makes up around a third of Vodafone’s business. Vodafone stands to lose around half of the 8.5 million TV customers who live in flats and other so-called “multi-dwelling units” this year because of new legislation that prevents landlords from bundling TV services into rental agreements.

I ask Della Valle if Vodafone might ever regain the reputation and buzz that it possessed back in the early 2000s. “I mean, we are talking about the very distant past,” she says. “I think where Vodafone is going is towards becoming much more flexible, fast and simple in the way it’s organised.”

Can she pull it off? Sir Roger Carr, a serial FTSE board member who recruited Della Valle as a non-executive director when he chaired Centrica in 2011, is confident she has it in her. “I think what they have with Margherita is somebody who is knowledgeable about the industry, has got genuine operational experience, but at the heart of her skillset is the financed thinking, which brings clarity and focus on solving business problems,” he says. “She’s demonstrated very quickly that, having been given the opportunity, she’s taken it and brought the necessary change.”

As for Della Valle, who describes herself as a “glass-half-empty CEO” who is never “completely satisfied about what we do and especially what I do”, she still feels there’s a long way to go. “We are a very different company today than we were a year ago,” she says. “But we are not yet a simple business. We are simpler, but there is more to come.”

The life of Margherita Della Valle

Born: April 13, 1965

Status: married to Alessandro with two sons, 29 and 26.

School: Lycée Albert Premier, a state school, in Monaco

University: Bocconi in Milan

First job: Strategic planning at an Italian chemical multinational Montedison

Pay: £4.38 million in salary, bonuses and benefits in 2023

Home: west London

Car: “I don’t have a car.” Husband has a “dark BMW”

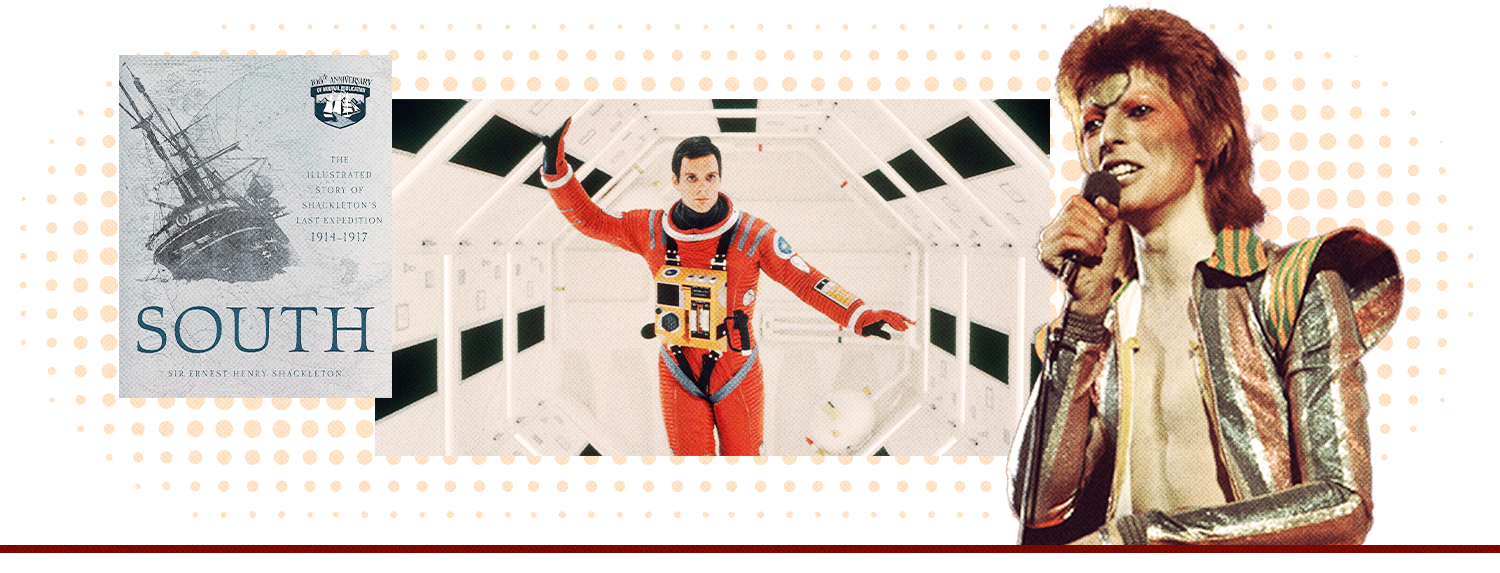

Favourite book: South by Ernest Shackleton

Film: 2001: A Space Odyssey

Music: David Bowie

Drink: decaf coffee and white wine

Watch: Apple

Gadget: miniature stackable jars that she uses to transport her make-up when travelling. “I’m always on the lookout on Amazon for what’s the latest travel hack.”

Last holiday: Japan

Charity: Vodafone Foundation. Della Valle is particularly passionate about the m-mama project, which aims to reduce childbirth mortality in Africa. M-mama has built up a network drivers who transport pregnant women in need of emergency care to hospitals.

WORKING DAY

Della Valle wakes up between 5.30 and 6am without the aid of an alarm clock. She takes 50 minutes to walk into work, arriving between 7.30 and 8am, and leaves around 12 hours later after a day of meetings. In the evening, she cooks, watches TV (Ted Lasso is one of her favourite series) and reads.

DOWNTIME

Walking along the Thames and stopping at pubs along the way, cooking, eating and reading.

Post Comment